New late blight strains are emerging at a rapid pace in Europe. They are aggressive and sometimes resistant to commonly used active substances. In years with high disease pressure, such as 2024, the situation is challenging. Decision Support Systems (DSS) help potato growers determine the best spraying timing. When disease pressure is low, they can potentially save (a lot of) money, according to Wageningen University & Research (WUR) researcher Geert Kessel. He has been studying the late blight fungus and the role that DSS systems play in this for years.

DSS systems have been around for at least thirty years. Yet Geert Kessel definitely does not want to say they are common practice among potato growers. “Cultivation advisors use them a lot, but not all arable farmers do. They grab the spray book and rely on their seven-day spray schedule for late blight control in potatoes. That's not always safe. We are seeing a growing group of innovative farmers who are becoming quicker at adopting digital technology especially if it is app-based.

Selection pressure

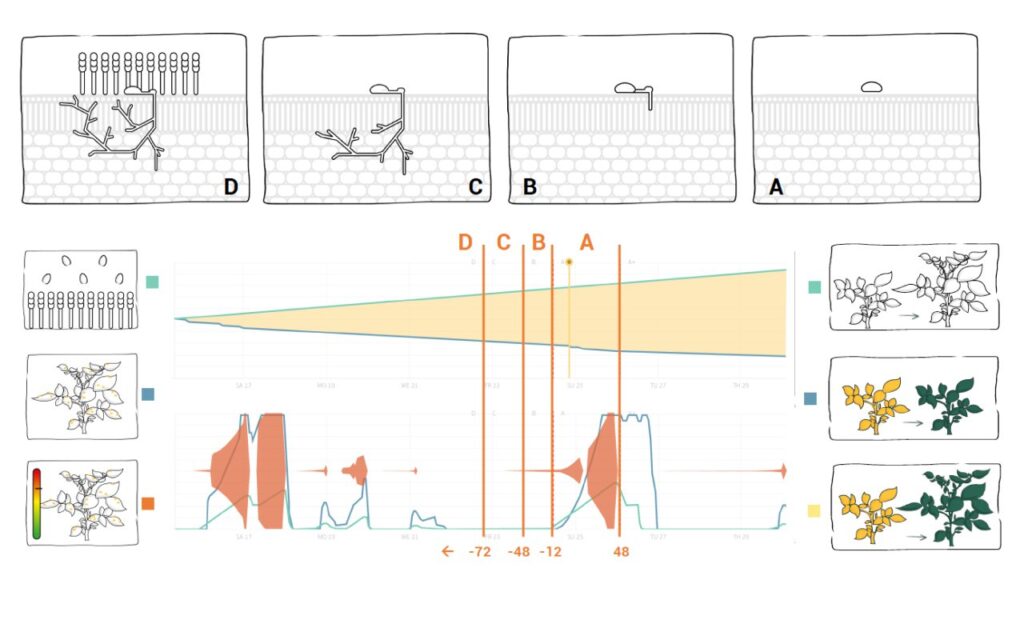

The summer of 2023 delivered exceptionally high late blight pressure in potato crops. A combination of favorable weather conditions and new strains resistant to, among other things, Revus (mandipropamid) and Zorvec (oxathiapiproline) contributed to the high disease pressure already starting early in the 2024 season. Late blight is rewriting the rules. The sector must anticipate this. “If you had predicted resistance to Revus three years ago, you would have been called crazy,” Kessel says. “By working with a narrow range of active substances, we exert selection pressure on late blight strains. That creates resistance. New mutations do not always result in increased aggressiveness. Nevertheless, overall, we see that the life cycle is getting shorter. The time between spore landing on the leaf and infection is now reduced to 2 to 5 days.”

‘Thinking from the fungus's perspective’

There are two important reasons to work with a DSS . What the system does is make clear how late blight will react to upcoming weather conditions. This can be done in roughly two ways, Kessel outlines. “All systems look at past weather data and the forecast to pinpoint a potential infection moment. One system places more weight on the protection duration of the substances you have used. The other system gives more weight to the pathogen's infection cycle. By essentially thinking from the pathogen's perspective, you can better predict where and when late blight will strike.” The CropX system also works according to this method. Dacom founder Jan Hadders was one of the pioneers in the field of DSS in the 1980s. It remains an important product for the company, which was acquired by CropX in 2021 and became CropX B.V. in 2024.

Not relying on farmers intuition

The systems from ten or twenty years ago are not comparable to the current ones, the WUR researcher notes. “Many growers have worked with them but sometimes got stuck.” Then it quickly gets set aside, and people rely on farmers' intuition. Because late blight is developing so quickly now, we can no longer afford that. The same applies to spraying in block schedules. The downside is that we now use more active substances, which contradicts political policy. It is important to alternate active substances so that natural selection and thus the risk of resistance do not get a chance.”

Saving money

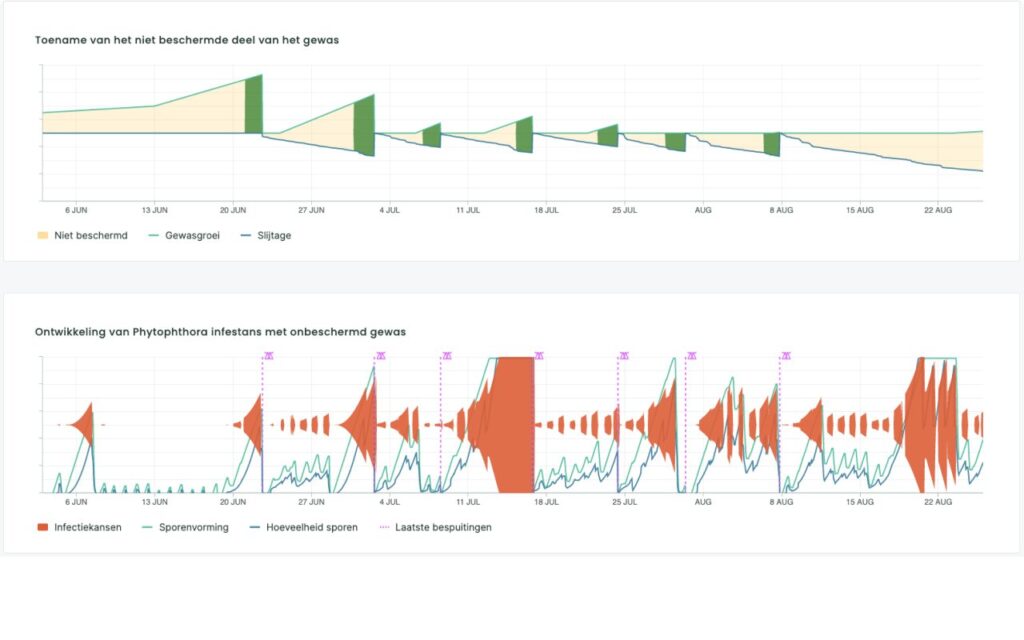

Can you blindly rely on the system's advice? Kessel emphasizes that as a grower, you must always think for yourself. “It helps you improve the timing of your spraying and is thus one of the measures you can take. If the disease pressure is low, you can extend the interval with the help of a DSS. Practical research by WUR has shown that you can quickly save 2 to 3 sprays per season. Therein lies the profit, even with few hectares, because costs are quickly 90 euros per hectare, per spray.” The system's theory and practice can also differ. “If the humidity is 1% higher for an hour, the DSS already responds to that. In practice, it is not yet a reason to take action. Some systems simply advise to spray or not to spray. What CropX does well is that their DSS has the intermediate class ‘consider spraying.’ As a grower, you can then decide for yourself.”

Don't be surprised

In de praktijk merkt Kessel dat de loofontwikkeling vaak wordt onderschat. “Als teler denk je misschien; ‘ik heb 2 of 3 dagen geleden nog gespoten’, maar dat is in een groeizame periode valse zekerheid. Sommige middelen bieden deels bescherming op nieuw blad. Een BOS-systeem kijkt wel naar de hoeveelheid onbeschermd blad en ziet zo dingen die je als teler misschien niet ziet. Anderzijds; als teler of adviseur weet je misschien dat er phytophthora-haarden in de buurt zijn. Die ziet het systeem dan weer niet.”

The advent of AI

With the rapid rise of AI (artificial intelligence), Kessel also sees new opportunities for DSS systems. “The current systems are based on process models. AI can help model the various infection steps. By overlaying various data layers, you make the system more reliable and self-learning.” The analysis of new mutations should also be faster, according to the late blight expert. A lot is monitored within the European Euroblight program (which Kessel is closely involved in), but the analysis is slow. “In an ideal scenario, an infection is recorded one day and analyzed and reported the next day. This way, growers do not have to use substances that no longer work. With the help of AI, a huge amount of complex data can be fed into the DSS without the grower noticing. Only their advice improves. We are moving further towards integrated crop protection with resistant and tolerant varieties, low-impact substances, and low environmental impact. When decision support systems combine all these factors and advise at the right moment, we improve crop protection.”

Would you like to learn more about CropX's disease management system? Feel free to contact us at service@dacom.nl for a trial subscription and expert advice.

About Geert Kessel

Geert Kessel studied plant pathology in Wageningen and has been working there as a researcher since 1999. He specializes in integrated crop protection, late blight control, and the development and use of decision support systems.